| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

https://dailynous.com/2023/08/08/the-social-turn-in-analytic-philosophy-promises-and-perils-guest-post/

The Social Turn in Analytic Philosophy: Promises and Perils (guest post)

"The linguistic turn is over. We partied hard, got hungover, and now we're trying to live as respectable adults… Today, a new revolution is brewing. Analytic philosophy is in the midst of a social turn."

This guest post is by Kevin Richardson, assistant professor of philosophy at Duke University, who brings together metaphysics, philosophy of language, and social philosophy in his work, writing about topics such as the metaphysics of social groups, social construction and indeterminacy, and ontological erasure. His post is about the "social turn" in analytic philosophy.

This is the eleventh in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

[Posts in the summer guest series will remain pinned to the top of the page for the remainder of the week in which they're published.]

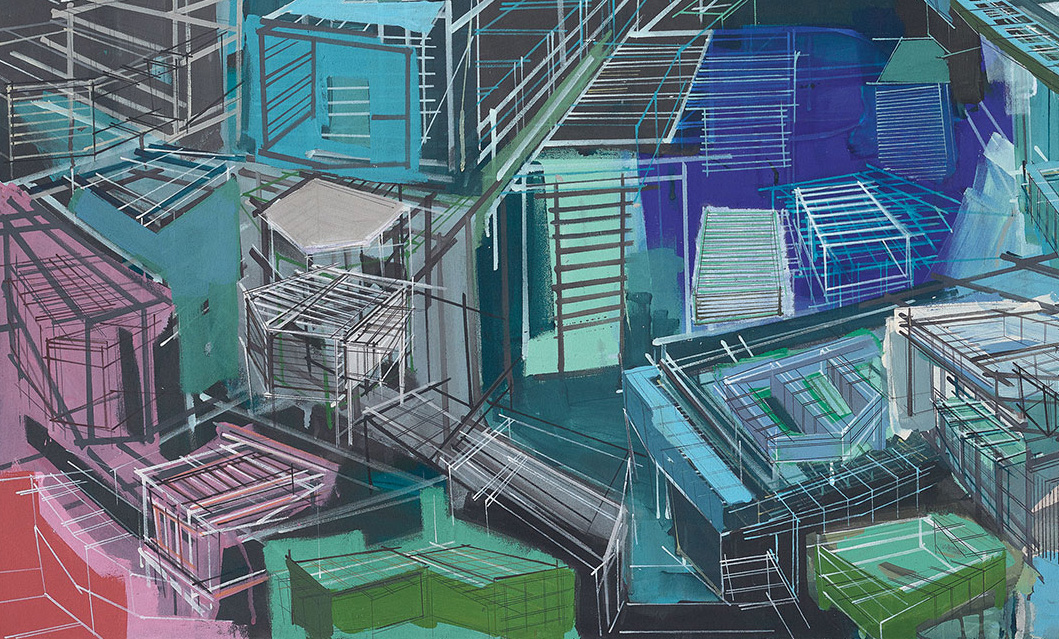

[Denyse Thomason, "Odyssey" (detail)]

The Social Turn in Analytic Philosophy: Promises and Perils

by Kevin Richardson

When I was a baby philosopher, I read Father Rorty religiously. Richard Rorty—the Patron Saint of Neo-Pragmatism, the analytic cousin of Jacques Derrida—edited a volume entitled The Linguistic Turn: Essays in Philosophical Method. Published in 1967, this anthology discussed the broad methodological shift toward language at the time.

Language was not only an important philosophical topic, but our approach to the study of metaphysics, epistemology, mind, and ethics principally required the analysis of language. Every philosophical subject would be approached through a linguistic lens.

I'm a 90's kid, so I didn't see the glorious linguistic turn in action. But I did go through a linguistic turn of my own, as an undergraduate. Robert Brandom and the Wittgensteinians convinced me that thought was impossible without language. I was a Goodmaniac: there is no Real World, only world versions. I tattooed the concluding section of Rudolf Carnap's "Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology" on my back. (I actually didn't do this but that was the energy back then.)

Of course, the linguistic turn is over. We partied hard, got hungover, and now we're trying to live as respectable adults. When our kids (students) ask about this period, we pretend we didn't partake.

Today, a new revolution is brewing. Analytic philosophy is in the midst of a social turn.

Every area of philosophy now has a thriving and lively socialized subfield. Social philosophers of language like Quill Kukla are discussing discursive injustice and analyzing the linguistic function of gendered discourse. Social epistemologists—e.g., Kristie Dotson, Miranda Fricker, Jennifer Lackey—are studying the ways that our epistemic practices contribute and constitute social injustice. Feminist philosophers of mind, such as Keya Maitra, consider the mind from an explicitly feminist perspective. Finally, social ontology—my own beloved field—is thriving more ever, thanks to the work of philosophical giants like Sally Haslanger.

Like a good analytic philosopher, you may question whether I can define a distinctively social turn in philosophy. After all, there's always been discussion of social philosophy, depending on what one means by "social." There are a few features of the social turn, as I understand it, that I want to highlight.

The social turn in philosophy is a critical turn. There is a broad agreement that we can do philosophy of language, metaphysics, epistemology, and so on, with the critique of injustice as an explicit theoretical aim. Ahem, I recently published a paper in Synthese, "Critical Social Ontology," in which I argue that fundamental metaphysics is well-suited for doing critical social ontology: social ontology done in order to critique ideology or eliminate social injustice. I draw from a rich history of feminist metaphysics. A similar dynamic exists in philosophy of language (conceptual engineering, new speech act theory) and epistemology (feminist epistemology, epistemology of ignorance).

Relatedly, the social turn is especially concerned with non-ideal (in the sense of actual or actually bad) conditions. Last year, Åsa Burman published a book called Non-Ideal Social Ontology. This year, Robin McKenna published a book called Non-Ideal Social Epistemology. The enterprising young philosopher of language should aim to publish Non-Ideal Social Philosophy of Language by 2025. (I expect to see myself in the acknowledgments, for the inspiration.) The attention to non-ideal conditions means that the social turn is concerned with what happens when things go wrong in the social world; it is not about The Social, abstractly conceived. In this way, the social turn is continuous with the trend in political philosophy toward non-ideal theory.

Finally, the social turn bridges the gap between "mainstream" metaphysics/language/epistemology and the subject matter of social philosophy. My distinctive genre of social ontology consists of mashing up analytic metaphysics (ground, essence, real definition, etc.) and social phenomena (gender, race, sexual orientation, social structures, etc.). Others have taken similar approaches to language and epistemology.

These three features make the social turn an exciting development in philosophy. The youth—I include myself here—are excited to do social philosophy. Asya Passinsky and I have organized a social ontology workshop for the last four years. Students and early-career scholars are typically more enthusiastic about social philosophy than their stated area of specialization. They say, "Kevin, I'm mainly interested in social [insert field here], but I have to put something else as my main area, in order to get job." Once these kids get a job or get promoted, they'll immediately make a social turn.

There are various reasons for the social turn. I suspect there may be a demographic shift that allows work in social philosophy to be taken more seriously. Or at least, there is less of a sense that social philosophy should be segregated from the rest of analytic philosophy. Another factor, I believe, is that social philosophy often feels more significant and interesting. As Dee Payton once said to me, social metaphysics is like metaphysics except fun.

With this in mind, I will briefly review a few promises of the social turn.

Promise #1: Popular appeal.

The social turn in philosophy is a great selling point to those critical of the worth of analytic philosophy. While I'm a fan of puzzles of modal variation and metaphysical grounding, the public is less interested in hearing about the modal flexibility of Flimsy the Bucket, and they definitely don't want to read my papers on grounding. (Hell, most people who work on grounding don't want to read my papers on grounding.) Social philosophy is great PR. Gender, race, sexual orientation—these are things that matter! At the very least, we may be able to get different kinds of students in philosophy. Students interested in social philosophy are more likely to enter the field if they think their work could be robustly supported by the profession. This may even help diversify the profession.

Promise #2: New philosophical terrain.

The social turn is great because it allows for new philosophical discoveries. If you want to write something new about the Special Composition Question, good luck! Those referees have a million papers that they think you should've read before submitting your paper. If you want to write about sex, you have a much better chance. (Even better: Sex and the Special Composition Question.) The point is that the social turn opens up new philosophical vistas. Junior academics can more easily establish themselves as new thinkers when they are in a field with significant amounts of unexplored terrain. This is good for the profession because, well, new philosophical subjects are exciting.

Promise #3: Increased potential for interdisciplinary work with other humanists.

A friend of mine is a literary scholar. One day she asked me what I've been reading lately. I was reading something on mereology at the time. I started explaining it, informally, but she insisted on reading the text, so I handed it over to her. Seeing the various formal definitions of Supplementation Principles, she burst out laughing. She said, "No one in my field is going to be able to understand this." This is true of a large portion of analytic philosophy. To be clear: she didn't laugh because she was opposed to analytical rigor; rather, the form of analytical rigor exhibited in philosophy, combined with the kinds of subjects philosophers discuss, can be quite different from what other humanists are familiar with. Social philosophy, at least, has the potential for more interdisciplinary work with other humanists. I think the isolation of philosophy from the humanities is disastrous. The social turn could spark more collaboration with humanists.

Now for a few perils, of which there are many.

Peril #1: Plug-and-chug social philosophy.

Social philosophy can be conceived as the mechanical application of non-social concepts (like essence) to the social world. This kind of simplistic application can lead to uninteresting or bad work. The danger is a failure of fit. It may be that talking about social philosophy of language using the frameworks of speech act theory or Gricean implicature is wrong-headed. Social philosophy should not be "plug-and-chug."

Peril #2: Unrealistic expectations.

Social philosophy, at least insofar as it is critical, can create unrealistic expectations of practical significance. In my own experience, the practical or political implications of social philosophy are so exciting that they tend to be the only thing that audiences want to hear about. The social ontologist is expected to be a normative ethicist, political philosopher, and public policy expert, all rolled into one. When the social ontologist inevitably fails to deliver, they say "social ontology won't solve our social problems!" as if that was ever on the table in the first place.

Peril #3: Philosophical Columbusing.

Consider sexual orientation. There is relatively little written about sexual orientation in analytic philosophy journals. However, there is a ton of relevant work on sexual orientation in non-analytic or non-philosophy journals. Philosophers, as Eric Schwitzgebel has pointed out, don't like to cite. Citation rates in philosophy are very low. Combine this with the fact that there's a lot of social philosophy that has existed prior to the social turn, and we have a recipe for philosophical Columbusing—the act of pretending to discover (or mistakenly thinking that one has discovered) a philosophical insight that has already existed.

There you have it. A new movement in philosophy—the social turn—along with its promises and perils. Like the linguistic turn, we will probably go overboard with our analytical rigor. (I am drafting my paper on topological theories of sexual orientation as we speak.) We will also probably overstate the significance of the turn: "Philosophy has been reborn!" we will say to each other at conferences.

Still, philosophy tends to be richer after it emerges from these bouts of irrational exuberance. With that in mind, I invite you to raise your glass and join me in a toast: to the social turn, let it change the shape of philosophy for the remainder of the twenty-first century. (With a nod to changing the world instead of only interpreting it, and all that.)

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿