https://jshet.net/docs/conference/79th/sakai.pdf

http://nam-students.blogspot.jp/2015/10/1979-john-maynard-keynes-treatise-money.html

ロウソク業者の請願 Petition of Candlemakers 1845- kurakenyaのつれづれ日記

https://kurakenya.hatenablog.com/entry/20101228 ★ーーー

リスク論1921,#12

《国家の役割は、人間関係を、相互自発的又は契約的なものに限るだけのことである》という指摘などはプルードンに近い。邦訳431頁

いやスピノザか?

ーー

ナイト1921より

#7

論理的な正確さのために、また、実際にそれらに対処するさまざまな種類の状況や方法を理解するためには、さらに別の区別をしなければならない。ある数値的な割合のXがYでもあるという形式の確率判断に到達するためには、基本的に2つの異なる方法がある。第一の方法は、先験的な計算によるものであり、偶然性のゲームに適用され、使用される。これもまた、確率の論理的・数学的処理で通常想定されるケースである。これは,計算が不可能であり,実例に統計を適用する経験的方法によって結果が得られるという全く異なるタイプの問題と強く対照的でなければならない.最初のタイプの確率の例として,完璧なダイスを投げる問題を考えてみましょう.もしそのダイスが本当に完璧であることがわかっているならば,そのダイスがある面に当たる確率を確かめるために,数十万回投げてみるのは単にばかげているだけである.仮にその実験が

ーー

経済的自由とは、経済的権力を行使する自由であり、その結果、その内容は、経済的権力の配分に応じて、奴隷から他者の奴隷化に至るまで、多岐にわたる可能性があるということである。彼らは、権力を利用してより多くの権力を得る自由が、不平等への累積的な傾向を伴うことに気づかずに、相続人の状態を含めて、すべての人の状態をより良くしたいという願望にさえ訴えた。(6) 歴史と歴史的因果関係に注目することで、「アプローチ」の異質な集団が生まれる。すでに述べたように、この立場は、説明が定常経済の抽象的な前提を超えて、内容や内容の変化を扱う場合には、常に関与している。これは、マルクス主義と呼ばれるようになった信条の第一条であり、経済的概念を批判的に扱ったことのない歴史家に大きく飲み込まれている。歴史家が歴史の経済的解釈を説く一方で、経済学者は経済学の歴史的解釈に向かって努力する。要するに、経済生活に影響を与える条件の変化は、それ自体が「合理的な」禁欲(「待つ」ではなく)と投資の結果であるならば、そしてその限りにおいて、経済学的な用語で説明することができる。これは、欲求、資源、技術に影響を与える変化の3つの分野に適用される。現在と未来のバランスを他の経済比較と同様に見ることに意味がないわけではない。しかし、すでに述べた動機の経済学的見解のすべての制限に加えて、現在を未来に犠牲にすることは、これらすべての点で反対のもののために、かなり即時的で、明確で、予測可能で、安全な未来を犠牲にすることを必然的に意味し、選択をする人の寿命を主に超えていることが知られています。経済発展は、収入に「現在の商品」の永久的な変換を含み、実際に永久に小さなものに短い期間のための大きな収入。この場合の真の動機は、消費の真の動機が大きく、すなわち象徴的で抽象的なものであるのとほとんど、あるいはまったく同じものである。私は、古典的伝統が、均衡に向けた動きを含む、与えられた条件の下でのシステムの働きと、与えられた条件やシステム自体の内容の変化とを、鋭く正しく理論的に区別することに失敗したことを、古典的伝統の大きな誤りの一つと考えなければならないし、今でも大きく失敗していると考えなければならない。このことは、経済力学という概念が、このような歴史的変化に言及するために誤解を招くような使い方をしていることにも反映されています。関連した誤りは、歴史的変化を均衡に向かう傾向があるものとして扱うことである。それらのどれも、不可逆性の考えも関与しているが、歴史的変化の定義として取られるかもしれない文は、言葉の適切な意味でそうしていない。歴史的変化は、むしろ、一般的には、自己強化的または累積的なものである。何らかの激変や退廃の神秘的な道徳的現象が介入しない限り、(どのような方向であれ)進歩はさらなる進歩への道を開く。歴史的変化は成長と呼ばれるべきではありません。

革命的社会主義の成長は、J.S.ミルの『政治経済学』(1848 年)と同じ年に共産主義宣言が出版されたことから始まると考えられる。第一次世界大戦におけるロシアでのマルクス主義の勝利は、イタリアとドイツでの反共産党への議会制の降伏と、他の地域での同様の変化に続いた。また、イギリスとアメリカでは、前者では社会主義政党が政権に就いたことによって特徴づけられた、さまざまな形態の経済国家主義の成長が見られる。この広範な変化によって提起された広大な問題についての議論に着手することなく、本書の解釈に関連するいくつかのコメントを記録しておきたい。第一に、私は、古典的な経済学や価格力学的なタイプの経済学に関して一般的に表現されている見解の誤りを強調しなければならない。この誤った見解は、発展の時間的偶然性という歴史的事実によって示唆され、強制されており、分析の多くの詳細については、それは真実である。しかし、根本的なことに関しては、二つの理由から、それは誤りである。第一に、社会主義的な運動も権威主義的な運動も、具体的な経済組織の主要な特徴である市場(多かれ少なかれ自由)での金銭による商品やサービスの売買をなくそうとしたり、真剣に提案したりすることはない。これは、近代的な意味での文明から原始的な生活様式への回帰なしには不可能であろう。資源の配分、生産の技術的な実施、製品の配給は、たとえ個人の自由への関心がすべて捨てられたとしても、非常に困難な行政上の問題を引き起こすであろう。(財とサービスのための開かれた市場こそが、消費者と生産者の双方に選択の自由を与えるとともに、相互利益のための大規模な協力を提供できる唯一のメカニズムであることは、論じるまでもないでしょう)。しかし、第二に、分析経済学のより一般的な原則は、社会的・政治的形態にかかわらず、個人や集団が手段を用いて効果的に目的を達成するという経済行動の原則にすぎない。ファラオ」の下でも、絶対的な主権と人間自身や土地や商品の完全な所有権を組み合わせても、無駄で無駄な活動ではなく、効果的な活動をするためには、同じ選択と決定がなされなければならないだろう。第二に、最後の言葉として、私は社会倫理的な信仰、あるいはイデオロギー的な立場を簡潔に宣言するかもしれません。もちろん、私は文字通りの「貸し借り」を信じているわけではありません。確かに、スミスやリカルドも、コブデンやブライトも、国家を個人の自由と外部からの攻撃に対する防衛という負の機能に完全に制限することはしなかっただろう。誰も「人間は社会的な動物である」ということを否定しないし、実際には社会は人間が社会を作るよりもはるかに多くの人間を作り、意図的な思考と行動によって意味する。しかし、私は個人主義が知的で道徳的に真面目な人の政治哲学でなければならないと信じています。選択肢は、人々が相互の同意によって協会の一般的な形式と条件を修正することを許可することとの間にある。

grown revolutionary socialism may be dated from the publication of the Communist Manifesto in the same year as J. S. Mill’s Political Economy, 1848. The triumph of Marxism in Russia in World War I was followed by the surrender of parliamentary regimes to anticommunist parties in Italy and Germany and similar changes elsewhere; and equally symptomatic is the growth of economic stateism of divers forms in Britain and America, marked by the accession to power of a socialistic party in the former. Without embarking here on any discussion of the vast issues raised by this broad sweep of change, I wish to record a few comments which are pertinent to the interpretation of the present book. First, I must stress the fallacy of the view so commonly expressed with respect to the classical or price-mechanics type of economics, that it is descriptively or practically relevant only to societies economically organised on the pattern of modern capitalism or free enterprise. This erroneous view is suggested and enforced by the historical fact of temporal coincidence of development, and for many details of the analysis it is true. But with respect to fundamentals, it is false, for two reasons. In the first place, no socialistic or authoritarian movement tries or seriously proposes to do away with the purchase and sale of goods and services for money, in markets (more or less free), as the main feature of economic organisation in the concrete. This would not be possible without reverting from civilisation in the modern sense back to a primitive mode of life; for, the allocation of resources, technical conduct of production and rationing of product would present an insuperable administrative problem, even if all concern for individual liberty were thrown into discard. (It should not need to be argued that the open market for goods and services is the only mechanism that can provide for large-scale co-operation for mutual advantages along with freedom of choice to both consumers and producers.) But in the second place, the more general principles of analytic economics are simply the principles of economic behaviour, of the effective achievement of ends by use of means, by individuals and groups, irrespective of social and political forms. Even under a “pharoah”, combining absolute sovereignty with outright ownership of men themselves as well as the land and goods, much the same choices and decisions would have to be made to make activity effective rather than wasteful and futile; and the abstract principles of economy and of organisation are the same regardless of who makes the choices, or what means and techniques are employed, or what ends are pursued. Secondly, as a last word, I may offer a brief declaration of social-ethical faith, or ideological position. Of course I do not believe in literal “laisser-faire” ; I know of no reputable economist who ever did. Certainly neither Smith and Ricardo nor Cobden and Bright would have restricted the state entirely to the negative functions of policing individual liberty and defense against outside attack. No one denies that “man is a social animal” ; and in fact society makes men far more than men make society, meaning by deliberate thinking and action. Yet I believe that individualism must be the political philosophy of intelligent and morally serious men. The choice lies between allowing people to fix the general form and terms of association by mutual consent, and having

What is The Candle Maker's Petition?

https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/08/candle-makers-petition.aspWhat Is the 'Candle Maker's Petition'?

The "Candle Maker's Petition" is a satire of protectionist tariffs, written the by great French economist Frederic Bastiat. In many ways, it expanded on the free market argument against mercantilism set forth by Adam Smith, but Bastiat targeted government tariffs that were levied to protect domestic industries from competition.

In Bastiat's "Petition," all the people involved in the French lighting industry, including "the manufacturers of candles, tapers, lanterns, sticks, street lamps, snuffers, and extinguishers, and from producers of tallow, oil, resin, alcohol, and generally of everything connected with lighting" call upon the French government to take protective action against unfair competition from the sun. It argues sarcastically: "We candlemakers are suffering from the unfair competition of a foreign rival."

Key Takeaways

- The "Candle Maker's Petition" was a complaint written by French economist Bastiat to his government to oppose import tariffs.

- Bastiat instead favored free markets for international trade and competition and that tariffs would have negative unintended consequences.

- Despite the economic theory underlying Bastiat's argument, protectionism still remains a tool used by governments in the global market.

Bastiat's Argument Against Tariffs

They argue that forcing people to close "all windows, dormers, skylights, inside and outside shutters, curtains, casements, bull's-eyes, deadlights, and blinds—in short, all openings, holes, chinks, and fissures through which the light of the sun is wont to enter houses"—will lead to a higher consumption of candles and related products. In turn, they reason, the industries that those in the lighting industry depend on for materials will have greater sales, as will their dependent suppliers, and so on—until everyone is better off without the sun.

This satirical essay suggests that forcing people to pay for something when a free alternative is available is often a waste of resources. In this case, the money people spend on additional lighting products would indeed boost the candle makers' profit, but because this expenditure is not required, it is wasteful and diverts money from other products. Rather than producing wealth, satisfying the candle maker's petition would lower overall disposable income by needlessly raising everyone's costs.

Similarly, using tariffs to force people to pay more for domestic goods when cheaper foreign imports are available allows domestic producers to survive natural competition, but costs everyone as a whole. Additionally, the money put into an uncompetitive company would be more efficiently placed into an industry in which domestic companies have a competitive advantage.

Bastiat concludes with the following remark:

Make your choice, but be logical; for as long as you ban, as you do, foreign coal, iron, wheat, and textiles, in proportion as their price approaches zero, how inconsistent it would be to admit the light of the sun, whose price is zero all day long!

Trade forex and CFDs on stock indices, commodities, metals and energies with a licensed and regulated broker. For all clients who open their first real account, XMTrading offers a ¥3000 trading bonus to test the XMTrading products and services without any initial deposit needed. Learn moreabout how you can trade from your PC and Mac, or from a variety of mobile devices.

A PETITION

From the Manufacturers of Candles, Tapers, Lanterns, sticks, Street Lamps, Snuffers, and Extinguishers, and from Producers of Tallow, Oil, Resin, Alcohol, and Generally of Everything Connected with Lighting.

To the Honourable Members of the Chamber of Deputies.

Open letter to the French Parliament, originally published in 1845 (Note of the Web Publisher)

Gentlemen:

You are on the right track. You reject abstract theories and have little regard for abundance and low prices. You concern yourselves mainly with the fate of the producer. You wish to free him from foreign competition, that is, to reserve the domestic market for domestic industry.

We come to offer you a wonderful opportunity for your — what shall we call it? Your theory? No, nothing is more deceptive than theory. Your doctrine? Your system? Your principle? But you dislike doctrines, you have a horror of systems, as for principles, you deny that there are any in political economy; therefore we shall call it your practice — your practice without theory and without principle.

We are suffering from the ruinous competition of a rival who apparently works under conditions so far superior to our own for the production of light that he is flooding the domestic market with it at an incredibly low price; for the moment he appears, our sales cease, all the consumers turn to him, and a branch of French industry whose ramifications are innumerable is all at once reduced to complete stagnation. This rival, which is none other than the sun, is waging war on us so mercilessly we suspect he is being stirred up against us by perfidious Albion (excellent diplomacy nowadays!), particularly because he has for that haughty island a respect that he does not show for us[1].

We ask you to be so good as to pass a law requiring the closing of all windows, dormers, skylights, inside and outside shutters, curtains, casements, bull's-eyes, deadlights, and blinds — in short, all openings, holes, chinks, and fissures through which the light of the sun is wont to enter houses, to the detriment of the fair industries with which, we are proud to say, we have endowed the country, a country that cannot, without betraying ingratitude, abandon us today to so unequal a combat.

Be good enough, honourable deputies, to take our request seriously, and do not reject it without at least hearing the reasons that we have to advance in its support.

First, if you shut off as much as possible all access to natural light, and thereby create a need for artificial light, what industry in France will not ultimately be encouraged?

If France consumes more tallow, there will have to be more cattle and sheep, and, consequently, we shall see an increase in cleared fields, meat, wool, leather, and especially manure, the basis of all agricultural wealth.

If France consumes more oil, we shall see an expansion in the cultivation of the poppy, the olive, and rapeseed. These rich yet soil-exhausting plants will come at just the right time to enable us to put to profitable use the increased fertility that the breeding of cattle will impart to the land.

Our moors will be covered with resinous trees. Numerous swarms of bees will gather from our mountains the perfumed treasures that today waste their fragrance, like the flowers from which they emanate. Thus, there is not one branch of agriculture that would not undergo a great expansion.

The same holds true of shipping. Thousands of vessels will engage in whaling, and in a short time we shall have a fleet capable of upholding the honour of France and of gratifying the patriotic aspirations of the undersigned petitioners, chandlers, etc.

But what shall we say of the specialities of Parisian manufacture? Henceforth you will behold gilding, bronze, and crystal in candlesticks, in lamps, in chandeliers, in candelabra sparkling in spacious emporia compared with which those of today are but stalls.

There is no needy resin-collector on the heights of his sand dunes, no poor miner in the depths of his black pit, who will not receive higher wages and enjoy increased prosperity.

It needs but a little reflection, gentlemen, to be convinced that there is perhaps not one Frenchman, from the wealthy stockholder of the Anzin Company to the humblest vendor of matches, whose condition would not be improved by the success of our petition.

We anticipate your objections, gentlemen; but there is not a single one of them that you have not picked up from the musty old books of the advocates of free trade. We defy you to utter a word against us that will not instantly rebound against yourselves and the principle behind all your policy.

Will you tell us that, though we may gain by this protection, France will not gain at all, because the consumer will bear the expense?

We have our answer ready:

You no longer have the right to invoke the interests of the consumer. You have sacrificed him whenever you have found his interests opposed to those of the producer. You have done so in order to encourage industry and to increase employment. For the same reason you ought to do so this time too.

Indeed, you yourselves have anticipated this objection. When told that the consumer has a stake in the free entry of iron, coal, sesame, wheat, and textiles, ``Yes,'' you reply, ``but the producer has a stake in their exclusion.'' Very well, surely if consumers have a stake in the admission of natural light, producers have a stake in its interdiction.

``But,'' you may still say, ``the producer and the consumer are one and the same person. If the manufacturer profits by protection, he will make the farmer prosperous. Contrariwise, if agriculture is prosperous, it will open markets for manufactured goods.'' Very well, If you grant us a monopoly over the production of lighting during the day, first of all we shall buy large amounts of tallow, charcoal, oil, resin, wax, alcohol, silver, iron, bronze, and crystal, to supply our industry; and, moreover, we and our numerous suppliers, having become rich, will consume a great deal and spread prosperity into all areas of domestic industry.

Will you say that the light of the sun is a gratuitous gift of Nature, and that to reject such gifts would be to reject wealth itself under the pretext of encouraging the means of acquiring it?

But if you take this position, you strike a mortal blow at your own policy; remember that up to now you have always excluded foreign goods because and in proportion as they approximate gratuitous gifts. You have only half as good a reason for complying with the demands of other monopolists as you have for granting our petition, which is in complete accord with your established policy; and to reject our demands precisely because they are better founded than anyone else's would be tantamount to accepting the equation: + ✕ + = -; in other words, it would be to heap absurdity upon absurdity.

Labour and Nature collaborate in varying proportions, depending upon the country and the climate, in the production of a commodity. The part that Nature contributes is always free of charge; it is the part contributed by human labour that constitutes value and is paid for.

If an orange from Lisbon sells for half the price of an orange from Paris, it is because the natural heat of the sun, which is, of course, free of charge, does for the former what the latter owes to artificial heating, which necessarily has to be paid for in the market.

Thus, when an orange reaches us from Portugal, one can say that it is given to us half free of charge, or, in other words, at half price as compared with those from Paris.

Now, it is precisely on the basis of its being semigratuitous (pardon the word) that you maintain it should be barred. You ask: ``How can French labour withstand the competition of foreign labour when the former has to do all the work, whereas the latter has to do only half, the sun taking care of the rest?'' But if the fact that a product is half free of charge leads you to exclude it from competition, how can its being totally free of charge induce you to admit it into competition? Either you are not consistent, or you should, after excluding what is half free of charge as harmful to our domestic industry, exclude what is totally gratuitous with all the more reason and with twice the zeal.

To take another example: When a product — coal, iron, wheat, or textiles — comes to us from abroad, and when we can acquire it for less labour than if we produced it ourselves, the difference is a gratuitous gift that is conferred up on us. The size of this gift is proportionate to the extent of this difference. It is a quarter, a half, or three-quarters of the value of the product if the foreigner asks of us only three-quarters, one-half, or one-quarter as high a price. It is as complete as it can be when the donor, like the sun in providing us with light, asks nothing from us. The question, and we pose it formally, is whether what you desire for France is the benefit of consumption free of charge or the alleged advantages of onerous production. Make your choice, but be logical; for as long as you ban, as you do, foreign coal, iron, wheat, and textiles, in proportion as their price approaches zero, how inconsistent it would be to admit the light of the sun, whose price is zero all day long!

Frédéric Bastiat

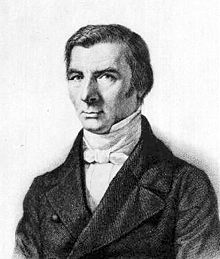

Claude-Frédéric Bastiat (/ˌbɑːstiˈɑː/; French: [klod fʁedeʁik bastja]; 30 June 1801 – 24 December 1850) was a French economist, writer and a prominent member of the French Liberal School.[1]

A Freemason and a member of the French National Assembly, Bastiat developed the economic concept of opportunity cost and introduced the parable of the broken window.[2]

As an advocate of classical economics and the economics of Adam Smith, his views favored a free market and influenced the Austrian School.[3]

Biography

Works

Economic Sophisms and the candlemakers' petition

Contained within Economic Sophisms is the satirical parable known as the candlemakers' petition in which candlemakers and tallow producers lobby the Chamber of Deputies of the French July Monarchy (1830–1848) to block out the Sun to prevent its unfair competition with their products.[8] Also included in the Sophisms is a facetious petition to the king asking for a law forbidding the usage of everyone's right hand, based on a presumption by some of his contemporaries that more difficulty means more work and more work means more wealth.[9]

経済ソフィズムとキャンドルメーカーの嘆願書

経済的なSophismsの内に含まれている風刺的な例え話として知られている燭台職人の嘆願書は燭台職人とタロウの生産者が彼らのプロダクトとの不公平な競争を防ぐために太陽を遮断するためにフランスの7月の君主制(1830-1848)の下院にロビー活動をする燭台職人の嘆願書として知られています。[8] また、「ソフィズム」には、より困難なことはより多くの仕事を意味し、より多くの仕事はより多くの富を意味するという彼の同時代人のいくつかの推定に基づいて、すべての人の右手の使用を禁止する法律を求める王への表向きの請願書も含まれている[9]。

8.9

- Bastiat, Frédéric. "Candlemakers' petition" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2005. Retrieved 12 December 2008.

- ^ "Bastiat: Economic Sophisms, Series 2, Chapter 16". Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

Views

Bastiat's tomb

Books

- Bastiat, Frédéric (1848). Propriété et loi, Justice et fraternité (in French). Paris: Guillaumin et Cie. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Bastiat, Frédéric (1849). L'État, Maudit argent (in French). Paris: Guillaumin et Cie. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Bastiat, frédéric (1849). Incomptabilités parlementaires (in French). Paris: Guillaumin et Cie. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Bastiat, Frédéric (1849). Paix et liberté ou le budget républicain (in French). Paris: Guillaumin et Cie. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Bastiat, Frédéric (1849). Protectionisme et communisme (in French). Paris: Guillaumin et Cie. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Bastiat, Frédéric (1983). Oeuvres économiques. Libre échange (in French). Textes présentés par Florin Aftalion. Paris: PUF. ISBN 978-2-13-037861-7.

- Bastiat, Frédéric (2005). Sophismes économiques. Bibliothèque classique de la liberté (in French). Préface de Michel Leter. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 978-2-251-39038-3.

- Bastiat, Frédéric (2009). Pamphlets. Bibliothèque classique de la liberté (in French). Préface de Michel Leter. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 978-2-251-39049-9.

See also

References

Further reading

External links

- Walter, Emile (del Mar, Alexander, pseud.) (1867). What is free trade? An adaptation of Frederick Bastiat's "Sophismes economiques". New York: G.P. Putnam and Son, repr. Dodo Press. ISBN 978-1-4099-3812-5.

ロウソク業者の請願 Petition of Candlemakers - kurakenyaのつれづれ日記

https://kurakenya.hatenablog.com/entry/20101228ロウソク業者の請願 Petition of Candlemakers

なんか、不明の理由から職場のサーバーが死んで長い間が経ちました。そこで、今後はすべてのファイルを「はてな」に移し、ホームページは、ペラ1枚にしてkurakenya.jimdo.comあたりにでもにつくろうかと思い立ちました。現在製作中なので、あまりできていません。

今一度自分のサイトを見てみると、かつてpdfにしたすべてのファイルが死んでしまっているのが残念です。とりあえず今日のところは、以下にBastiat バスティアの「請願書 A petition 」を再掲します。あと、驚いたことに「見えるものと見えないもの」をippatsu1234さんという方がyoutubeに載せてくれていました。

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=veJgPJfp4Rw

だれか是非、この「請願書」もyoutubeに載せておいていただきたいとお願いします。

??????????????????????

http://www.panarchy.org/bastiat/petition.eng.1845.htmlより訳出

請願書

ロウソク、小ロウソク、ランタン、燭台、街灯、ロウソク消し、消火器に関わる製造業者、並びに、獣脂、植物油、樹脂、アルコール、そして照明に関連する一般的にすべての生産者より。

立法議会の名誉ある代議士各位へ。

方々

皆様は正しい方向に向かっておられます。それは抽象的な理論を拒否し、余剰や低価格ということについて関心を持っておられないこと、そして主に生産者の命運について御心配になっているということです。生産者を外国からの競争から解放しようとなさっていること、つまり、国内市場を国内産業にとっておくということです。

私たちは、皆様に対して、皆様の――何とお呼びすれば良いのでしょうか?皆様の理論?いいえ、理論ほど詐欺的なものはありません。皆様の原則?皆様の体系?皆様の原理?しかし皆様は原則などお嫌いですし、体系性には恐怖をお持ちです。そして原理につきましては、政治経済にはそんなものの存在を否定されています。ですから皆様の実践とお呼びしましょう――理論と原理のない実践を適用していただく素晴らしい機会をお持ちいたしました。

私たちは、外国の競合者からの破滅的な競争に苦しんでおります。競合者は明らかに我々の光の生産よりもはるかに優れた状況で働いており、信じられない低価格で国内市場に洪水のようにやってくるほどです。現在のところ、その様子は、私たちの売り上げはなくなり、すべての消費者は競合者に流れ、数え切れないほどの影響を持つフランス産業の一部門が、完全に停滞してしまうほどに減産しているのです。この競合者は、まさに太陽そのものなのですが、私たちに対してまったく無慈悲な戦いを挑んできており、その有様は、不誠実な白国1によってそそのかされている(今日においては、すばらしい外交政策です!)と私たちは憶測しているほどです。特にこのことは、太陽があの傲慢な島に対しては、私たちには示すことのない敬意を払っていることに明らかです。

私たちは、すべての窓、屋根窓、天窓、内外にある雨戸、カーテン、覆い、円形ガラス、ガラス窓、ブラインド、つまり、太陽光が屋内へと入りがちである、すべての開口部、穴部、隙間や割れ目、を閉めることを要求する立法を、皆様に通していただく道徳的公正さを求めております。それらが、我が国に与えられたと私たちが誇りを持って言える公正な産業の損失につながるのであり、我が国は、これまでの恩を裏切ることなしには、私たち業者をこれほど不公正な今日の競争状態に捨て置くことはできないのであります。

名誉ある代議士各位、私たちの要求を真剣に取り上げていただく公正さをお持ちいただき、そして少なくとも、私たちがこの議論を補強するために提出する理由をお聞きにならないままに拒否されることがありませぬようお願いいたします。

最初に、もし太陽光が入ってくることを出来るだけ遮断して、人工の需要を作り出すなら、一体フランスのどの産業が、最終的な拡大の利益を受けないというのでしょうか?

もしフランスがより多くの獣脂を消費するなら、牛や羊はもっと多くなり、その結果、開けた草地、肉、羊毛、皮革、そしてすべての農業的な富の基盤となる糞尿の増加につながるでしょう。

もしフランスがより多くの植物油を消費するなら、ケシ、オリーブ、アブラナの栽培の拡大につながります。これらの豊饒な、しかし土壌の養分を消耗してしまう植物は、牛の放牧によってより肥沃になった土地を有益に利用することを、まさに適切な時に可能にするのです。

フランスの原野は樹脂性の樹木で覆われるでしょう。無数のハチの群れが山々から、現在は無駄になっている芳しい財宝を、ちょうど花から出るもののように、集めてくるでしょう。よって、大きく飛躍することのない農業分野は一つとしてないのです。

同じことが運送についても当てはまります。何千もの船が捕鯨にいそしむことになり、間もなくのうちに、フランスの名誉の維持ならびに、請願書の署名者とロウソク業者、その他の者の愛国的な熱望を可能にするだけの海運力を獲得するでしょう。

しかし、パリの製造業者の特産品については何が言えるのでしょうか?これから皆様は、金装飾、青銅、そして水晶細工が、燭台やランプ、シャンデリア、装飾枝付きの燭台などにほどこされ、広大な商業広場にきらめくのを見ることでしょう。それらに比べれば、現在あるものなど、まがい物という程度でしかありません。

砂丘をのぼる困窮した樹脂の採集者、暗い穴の奥に行く貧乏な鉱夫といった、結局は、高い賃金を得られず、より大きな繁栄を享受することのできないような人もいなくなります。

方々、ほんの少しばかり考えただけで、アンザン株式会社の裕福な株主から最も小さなマッチ売りに至るまで、私たちの請願がかなうことによって状況が改善されないものなどフランス人にはおそらくいないことを確信されるでしょう。

方々、私たちは反論があるだろうことを知っています。しかし、それらのすべては自由貿易の信奉者によるカビ臭い古本に書かれていることです。私たちは、私たちに反対する意見が、皆様と皆様のすべての政策を導く原理に即座に反するものではない、という考えに挑戦いたします。

皆様は、この保護政策によって私たちは得をするものの、消費者がその負担を課されるということから、フランスは得るところがないとおっしゃるのでしょうか?

私たちの答えは、以下のように、すでに用意されています。

皆様は、もはや消費者の利益を引き合いに出す権利など持っていないのです。皆様は、消費者の利益が生産者の利益と反する場合には、常に消費者を犠牲にしてきました。それは産業を振興し、雇用を増大させるためでした。同じ理由から、皆様は今回もまたそうしなければならないのです。

実際、皆様自身がこのような反対を予想されていたでしょう。鉄、石炭、ゴマ、小麦、織物の市場への自由な参入が消費者の利益になるといわれた時、皆様は「そうだ、だが生産者はその締め出しから利益を得る」と答えられました。すばらしい!当然に、もし消費者が太陽光が入ることから利益を得るのであれば、生産者はその遮断から利益を得るのです。

皆様はなおもおっしゃるかもしれません。「しかし、生産者と消費者は同じ一人の人間なのだ。もし製造業者が保護によって利益を得るのであれば、彼らは農民をも繁栄させるだろう。その反対に、もし農業が発展していれば、それは製造された商品の市場をつくるだろう。」すばらしい!もし皆様が私たちに日中の光生産の独占権を与えていただけるなら、まず最初に私たちは、我々の産業に供給するために大量の獣脂、松脂、植物油、樹脂、蜜ろう、アルコール、銀、鉄、銅、そして水晶を購入いたします。そしてさらには、私たちとその無数の商品供給者が豊かになり、大量に消費して、国内産業のすべての領域に繁栄をもたらすのです。

皆様は、太陽光は自然からの無料の贈り物であり、それを利用する手段を促進するための言い訳として、それを拒否することは富を拒否することだとおっしゃるのでしょうか?

しかし、もし皆様がこのようにお考えであるのなら、皆様自身の政策に致命的な一撃を与えることになってしまいます。御記憶ですか、これまで皆様は、外国の商品を、それらが無料の贈り物である程度に応じて、あるいはそうであるために、排除してきました。皆様が他の独占業者からの要請に応じるための理由づけは、皆様の確立した政策に完全に適合している私たちの要請を許容するための半分でしかないのです。そして私たちの要求を、まさに他の者たちの要求よりもより理由付けられているという理由から拒否することは、+ x + = - という等式を受け入れることと同値なのです。つまり不条理に不条理を重ねるということです。

労働と自然は、国や気候に応じて異なった割合で、商品生産において協働します。自然が貢献する部分は常に無料です。そして人間の労働による貢献部分が価値を持つのであり、対価が支払われるべきなのです。

もしリスボンからのオレンジがパリからのオレンジの半額で売られるのだとしたら、それは太陽からの自然の熱、それはもちろん無料です、が、パリにおいては人工の熱によってなされることをリスボンでしてくれているからなのです。そして、人工の熱は市場における代償を支払わざるを得ません。

よって、ポルトガルからオレンジがやってくる場合、それは半分無料で提供されているといえるのです。あるいはまた別の言い方をすれば、パリのオレンジに比べると、半額で提供されているともいえるでしょう。

さて、まさしくそれらの準無料(この言葉をお許しください)ということに基づいて、皆様はそれらの禁輸を維持してこられました。皆様はおっしゃいます。「フランスではすべての仕事をしなければならないのに、外国ではその半分しかする必要がなく、残りは太陽がやってくれるのに、どうやってフランスの労働者は外国の労働者との競争に耐えられるというのだろうか?」しかし、もし生産物が半分無料であるという事実によって、皆様が競争から排除するというのであれば、完全に無料であるという事実によって、どうして皆様が競争に参入することをお許しになることができましょうか?つじつまが合わないことをお認めになるか、あるいは、半分無料のものを我が国の国内産業に有害であるとして排除した以上、完全に無料であるものもまったく同じ理由で、2倍の情熱を持って排除しなければなりません。

別の例を挙げてみましょう。石炭、鉄、小麦、織物といった産物が外国から来る場合、あるいはそれらを私たちが自分で生産するよりも少ない労働量によって獲得する場合、その差は私たちに与えられた無料の贈り物です。この贈り物の大きさは、その差に比例します。それは、外国人が国内価格の4分の4、半分、4分の1を要求する場合、その生産物の価値の4分の1、半分、4分の3なのです。このことは、ちょうど太陽が光を与えてくれる場合のように、送り手が何らの対価も求めない場合に、まったく完全に当てはまります。私たちがここで正式に提示する疑問とは、皆様がフランスに望むものが無料の消費からの便益であるのか、それとも面倒くさい生産というものにおける想像上の利益なのかということなのです。論理的になることなく、どちらかをお選びください。なぜなら、皆様がなさっているように、外国の石炭、鉄、小麦や織物を、その価格がゼロに近づくに比例して禁止する限り、一日中ただである太陽光をお許しになるというのは、なんとつじつまが合わないことでしょうか?

流れを予測できない、日銀の金融政策 | 小幡績の視点 | 東洋経済オンライン | 経済ニュースの新基準

返信削除https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/34222?page=2

流れを予測できない、日銀の金融政策

不確実性とは何か

それは、読めないからである。今日は、その話をしよう。

といっても、日銀の金融政策などというつまらない話ではない。実態的(ここでの実態は「実体」の要素もある)に影響のないものが、なぜ実体に影響を与えるのか。

それは不確実性があるからである。

では、不確実性とは何か。フランク・ナイトの不確実性と言ってもいいかもしれない。

ナイトの不確実性とは?

ナイトの不確実性は、予期できないものであり、確率分布として数量的に把握できないもの、というのが雑なまとめ方だが、リスクとは「数量化できるもの」、不確実性(uncertainty)とは「数量化できないもの」と分けるのが、安全な定義だ。

なぜなら、この定義は中身がないから、間違いになることはなく安全だからだ。

数量化できない不確実性とは何か。

ケインズの処女作は確率論(蓋然性)である。彼の確率論は、話題にはなかったが、ラムゼーなどの批判もあり、誤りであるということになっているが、理論化に失敗したとしても、ケインズの言いたいことは、客観確率とそれとは別のものがある、ということだった。後者の別のものとは、ナイトの不確実性と似たものであると思われる(私の個人的解釈だ)。

ここでは、この議論はやめて、要は、ナイトの不確実性だか、ケインズの客観的でないものだか、何らかの不思議なものが存在する、ということだ。

かつての流行の言葉で言えば、想定外、ということだろう。もっと意味不明の流行語で言えば、ブラックスワンだ。

いずれにせよ、これがいろいろなことをもたらす。

ナイトは、リスクと不確実性を区分した、ということになっているが、その著書のタイトルは “Risk, Uncertainty and Profit” だ。皆、3つめの言葉を忘れている。ここが重要だ。

つまり、リスクは事前に予期され、計算されるから、事後的な運不運はあるだろうが、宝くじと同じで、すべて予想通り、期待シナリオの一つだということだ。一方、不確実性は、全く予期も計算も、準備もできないから、これを捉えるには、経済主体により差が出る。そして、これが利益の源泉となる。このチャンスを捉えるのが、経営であり、企業組織であり、戦略である。

循環図のリンク内がリスクで

返信削除外が不確実性だ

『経済学のメソドロジー (叢書 ヒストリー・オヴ・アイディアズ) 』

返信削除F.H. ナイト (著), N. ジェオルジェスク・レージェン (著), K.E. ボールディング (著), K.J. アロー (著

)

平凡社 1988/3

【目次】

経済学の観念史

(経済学という観念/経済思想の進化における時代区分/三つの生産要素の誤謬/現代の科学的経済学における区分/成長を伴う市場経済秩序―資本と利子、地代と賃金の利潤/貨幣と利子率―景気循環)

自然的自由の経済理論

(概念の生成/パラダイムとしての自然的自由―影響・批判・可能性)

経済思想における効用と価値

社会的厚生の形代理論

(個人選択と価値/社会的厚生関数/社会的厚生と投票)

http://mixi.jp/view_item.pl?id=1229387

http://www.amazon.co.jp/exec/obidos/ASIN/4582733751

イイネ!コメント

[3] mixiユーザー

03月17日 04:39

『現代経済学の巨星〈上・下〉―自らが語る人生哲学』

M. シェンバーグ (編), 都留 重人 (監訳)

岩波書店 1994/11/10 1994/12/12

【内容】

なぜ経済学者になったのか。

現代経済学に大きな影響を及ぼしている22人の碩学が、経済学とその人生哲学について語る。

経済学は、知識と技術だけでなく、道徳哲学としての性格を持っているという共通の主張は、学問および人生にかんし、考え抜かれた示唆を提供している。

上巻執筆者はロビンソン、ティンベルヘン、ジョージェスク=レーゲン、ボールディング、キンドルバーガー、シトフキー、など。

【目次】

上巻

オースティン・ロビンソン―経済学者としての私の実習時代

ヤン・ティンベルヘン―最も緊急な問題をまず最初に解決しよう

ニコラス・ジョージェスク=レーゲン―自らを語る

ケネス・E・ボールディング―化学から経済学へ、そして経済学を超えて

チャールス・P・キンドルバーガー―私の仕事哲学

ティボール・シトフスキー―私の福祉への模索

リチャード・A・マスグレーヴ―社会科学と倫理と公共部門の役割

モーリス・アレ―研究に向けての情熱

http://mixi.jp/view_item.pl?id=3884942

http://www.amazon.co.jp/exec/obidos/ASIN/4000006312

下巻

科学的ヒューマニズムを理想とする

ある比較経済学者の回顧と反省

私はどのように経済学者になるべく努力したか

私の人生哲学―政策信条とその運用方法

政治経済学についての省察―過去、現在、そして未来

学際的な場に生きて

私の経済知識の探求〔ほか〕

http://mixi.jp/view_item.pl?id=3884943

http://www.amazon.co.jp/exec/obidos/ASIN/4000006320

第一章 合理的規範の探来

返信削除せている人々によってきばかれております。ここで、彼らと“真実。との関係が主要な問題になるの

ャ*中6ためにく編日見に訴えかけることを開囲せる何かが存在しているだけでなく、 その大

細中 に無見を基受することにあります。批判は にお ておりまして、何らかの自己

益を促進するために明白な意国をもって他人を欺いている、といった告発から、ごく一般的な種類の

非離に至るまで、実に様々です。そうした斜弾や説法は、後日、人間本性の特徴や客観的思考が堕落」

する主な原因として、詳しく検詩されなければなりません

保護主義について、個人的なことを差し挟ませて下さい。私自身、過去から受け継がれてきた偏見

でもって、この認見を支持しておりました。と申しますのも、私は幼い時分、共和党を支持する人た

ちのもとで、中西部の農場をヨチョチ歩いていたからです(ついでに付記すれば、この“階層, の大半は

彼ら自身の経済的利害とは真っ向から対立する保護賀易政策に賛成票を投じておりました)。私にとって、この一

偏見から自身を解き放つのがどれほど骨の折れることであったか。思い起こせば、実際に解放された

のは、大学レベルの経済学を勉強していた学生の頃でした。では政治に関する私の記憶はといえば、

はるか違く、一八九六年のマッキンリー[William MeKinley Jr. (一八四三1一九0-)共和党の政治家,

第三九代オハイオ州知事(一八九二~1八九六),第二五代アメリカ大統領(一八九七~一九〇1)]対プライア

A(Wilam Jennings Bryan(1八六〇1 一九二五) 民主党の政治家 w . ウイルソン政権下の第四一覧代国務長

* -トト

官(一九11三年1一五年)]の大統領選にまで 週、ります。そこでは、保護貿易政策とインフレ政策が

主な争点でした。古めかしく陳席なたわ言を売り込みに使う、共和党の選挙演説を覚えています。ア

メリカ人が外国人から商品を買うと、外国はお金を手に入れ、アメリカは商品を得るけれども、もし

外国人がアメリカ人から商品を買うのであれば、アメリカはお金も商品も両方手にできる、というの

です。そうした論法は、事実を指摘することに果たして何か意味があるのか、あるいは人はただ、真

珠の価値に気付かない生き物とでも申しましょうかーーの前へ真珠を投げ入れることによって

自らの知性に泥を塗り、面目を失っているだけではないのか、という疑問を生じさせます。そうした」

疑いは、もう一方の政党の熱烈な支持者たちが、この点については真実を理解しているように見える、

と指摘したからといって晴れることはないでしょうし、それどころか彼らは、同じくらい酷い他方の

見|ひとまとめとして特筆した、もう片方のインプレ政策

の選挙戦は、インフレを通じた繁栄から国民を遠ざけると同時に、最も効率的な生産者から消費者が

商品を買うことを容認してアメリカの労働者が貧しくなるのを防いだ、と言われております。人によ

レゼ Kトィア 【Claude F, Bastiat (|<O|-一 八五〇) フランスの経済学]間白おかしく感相

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書を連想し、太陽からやって来る安い外国産の好りとの破滅的な競争を

排すべく窓を禁止してほしい、といった請願だけでなく、このように逆手をとった行き過ぎた論法

[reductio ad absurdum] 田覚ましい感銘を生むことはない、 といった現実まで、想い起こしておら

ーに惚れ込み、夢中なのです。先述

....

れるかもしれません。

インフレの事例は、原理的には単純なくらいです。お金はただ、価値あるモノを他人の手からこち

らの手に入れるためにだけ役立つにすぎませんから、したがってもし仮に、より多くのお金が全ての

の

第一章 合理的規範の探求

返信削除メリカ人が外国人から商品を買うと、外国はお金を手に入れ、アメリカは商品を得るけれども、もし

外国人がアメリカ人から商品を買うのであれば、アメリカはお金も商品も両方手にできる、というの

です。そうした論法は、事実を指摘することに果たして何か意味があるのか、あるいは人はただ、真

珠の価値に気付かない生き物|とでも申しましょうか||の前へ真珠を投げ入れることによって、

自らの知性に泥を塗り、面目を失っているだけではないのか、という疑問を生じさせます。そうした

疑いは、もう一方の政党の熱烈な支持者たちが、この点については真実を理解しているように見える

と指摘したからといって晴れることはないでしょうし、それどころか彼らは、同じくらい酷い他方の

謬見| ひとまとめとして特筆した、もう片方のインフレ政策

の選挙戦は、インフレを通じた繁栄から国民を遠ざけると同時に、最も効率的な生産者から消費者が

*-トト ネ :

ーに惚れ込み、夢中なのです。先述

商品を買うことを容認してアメリカの労働者が貧しくなるのを防いだ、と言われております。人によ

っては、バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(1八〇一~一八五〇O)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造」

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書を連想し、太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を

排すべく窓を禁止してほしい、といった請願だけでなく、このように逆手をとった行き過ぎた論法

[reductio ad absurdum]が目覚ましい感銘を生むことはない、といった現実まで、想い起こしておら

れるかもしれません

インフレの事例は、原理的には単純なくらいです。お金はただ、価値あるモノを他人の手からこち

の

らの手に入れるためにだけ役立つにすぎませんから、したがってもし仮に、より多くのお金が全ての

せている人々によってさばかれております。ここで、彼らと“真実。との関係が主要な問題になるの

返信削除です。論争のために広く偏見に訴えかけることを通用させる何かが存在しているだけでなく、その大

部分は、論敵に偏見を転嫁することにあります。批判は多岐にわたっておりまして、何らかの自己利

益を促進するために明白な意図をもって他人を欺いている、といった告発から、ごく一般的な種類の

非難に至るまで、実に様々です。そうした糾弾や説法は、後日、人間本性の特徴や客観的思考が堕落

する主な原因として、詳しく検討されなければなりません

保護主義について、個人的なことを差し挟ませて下さい。私自身、過去から受け継がれてきた偏見

でもって、この謬見を支持しておりました。と申しますのも、私は幼い時分、共和党を支持する人た

ちのもとで、中西部の農場をヨチヨチ歩いていたからです(ついでに付記すれば、この“階層, の大半は、

彼ら自身の経済的利害とは真っ向から対立する保護貿易政策に賛成票を投じておりました)。私にとって、この

偏見から自身を解き放つのがどれほど骨の折れることであったか。思い起こせば、実際に解放された

のは、大学レベルの経済学を勉強していた学生の頃でした。では政治に関する私の記憶はといえば、

はるか遠く、 一八九六年のマッキンリー[William McKinley Jr. (1八四三~一九O 1)共和党の政治家

第三九代オハイオ州知事(一八九二~一八九六)第二五代アメリカ大統領(一八九七~一九〇1)] 対ブライア

ン[William Jennings Bryan(一八六〇~一九二五)民主党の政治家·W·ウィルソン政権下の第四一代国務長

* - ト*マ *.

官(一九1三年~一五年)]の大統領選にまで 遡 ります。そこでは、保護貿易政策とインフレ政策が

主な争点でした。古めかしく陳腐なたわ言を売り込みに使う、共和党の選挙演説を覚えています。ア

トンャンス

Title ケインズの哲学と経済学 Author(s) - 京都大学学術情報リポジトリ(Adobe PDF)

返信削除repository.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dspace/.../10155203.pdf

-キャッシュ

ケインズ(John Maynard Keynes)の初期の著書に「確率論」(A Treatise on Probability, 1921) "があるが,ケインズが20歳 ...

ケインズとナイト - 滋賀大学経済学部(Adobe PDF)

www.econ.shiga-u.ac.jp/risk/.../DPJ36Sakai201304.pdf

-キャッシュ

J. M. Keynes versus F. H. Knight: ... が、まさに 1921 年という同じ年に、リスク・確率や蓋然性・不確実性を主題にした ...

ナイト1960

返信削除商品を買うことを容認してアメリカの労働者が貧しくなるのを防いだ、と言われております。人によ

っては、バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(1八〇一~一八五〇O)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造」

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書を連想し、太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を

排すべく窓を禁止してほしい、といった請願だけでなく、このように逆手をとった行き過ぎた論法

[reductio ad absurdum]が目覚ましい感銘を生むことはない、といった現実まで、想い起こしておられるかもしれません。

ナイト2012^1960

9頁

バスティア1845

返信削除バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(1八〇一~一八五〇)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

返信削除したロウソク製造業者の陳情書を連想し、太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を

排すべく窓を禁止してほしい、といった請願1845

ナイト2012,9頁

バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(一八〇一~一八五〇)]フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

返信削除したロウソク製造業者の陳情書…太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を

排すべく窓を禁止してほしい、といった請願1845

ナイト2012,9頁

「太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を排すべく窓を禁止してほしい」

返信削除バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(一八〇一~一八五〇)]フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書1845

ロウソク業者の請願 Petition of Candlemakers - kurakenyaのつれづれ日記

https://kurakenya.hatenablog.com/entry/20101228

http://www.panarchy.org/bastiat/petition.eng.1845.html

http://bastiat.org/en/petition.html

「太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を排すべく窓を禁止してほしい」

返信削除バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(一八〇一~一八五〇)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書(1845年)

ロウソク業者の請願 Petition of Candlemakers - kurakenyaのつれづれ日記

https://kurakenya.hatenablog.com/entry/20101228

http://www.panarchy.org/bastiat/petition.eng.1845.html

http://bastiat.org/en/petition.html

リスク、不確実性、利潤 (単行本) 単行本(ソフトカバー) – 2021/8/2

返信削除フランク・H・ナイト (著), 桂木 隆夫 (翻訳), & 2 その他

20世紀の経済学に大きな影響を与えた理論経済学者・ナイト。資本主義の原理を追究し、企業経営の本質に迫り、営利の源泉を喝破した主著にして名著を新訳で刊行。

フランク・ナイト社会哲学を語る―講義録 知性と民主的行動 単行本 – 2012/12/1

返信削除フランク ナイト (著), & 2 その他

ナイト1960

商品を買うことを容認してアメリカの労働者が貧しくなるのを防いだ、と言われております。人によ

っては、バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(1八〇一~一八五〇O)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造」

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書を連想し、太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を

排すべく窓を禁止してほしい、といった請願だけでなく、このように逆手をとった行き過ぎた論法

[reductio ad absurdum]が目覚ましい感銘を生むことはない、といった現実まで、想い起こしておられるかもしれません。

ナイト2012^1960

9頁

「太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を排すべく窓を禁止してほしい」

バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(一八〇一~一八五〇)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書(1845年)

ロウソク業者の請願 Petition of Candlemakers - kurakenyaのつれづれ日記

https://kurakenya.hatenablog.com/entry/20101228

http://www.panarchy.org/bastiat/petition.eng.1845.html

http://bastiat.org/en/petition.html

返信削除フランク・ナイト社会哲学を語る―講義録 知性と民主的行動 単行本 – 2012/12/1

フランク ナイト (著), & 2 その他

ナイト1960

商品を買うことを容認してアメリカの労働者が貧しくなるのを防いだ、と言われております。人によ

っては、バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(1八〇一~一八五〇O)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書を連想し、太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を

排すべく窓を禁止してほしい、といった請願だけでなく、このように逆手をとった行き過ぎた論法

[reductio ad absurdum]が目覚ましい感銘を生むことはない、といった現実まで、想い起こしておら

れるかもしれません。

ナイト2012^1960、9頁

「太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を排すべく窓を禁止してほしい」

バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(一八〇一~一八五〇)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書(1845年)

ロウソク業者の請願 Petition of Candlemakers - kurakenyaのつれづれ日記

https://kurakenya.hatenablog.com/entry/20101228

http://www.panarchy.org/bastiat/petition.eng.1845.html

http://bastiat.org/en/petition.html

返信削除フランク・ナイト社会哲学を語る―講義録 知性と民主的行動 単行本 – 2012/12/1

フランク ナイト (著)

《商品を買うことを容認してアメリカの労働者が貧しくなるのを防いだ、と言われております。人によ

っては、バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(1八〇一~一八五〇O)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書を連想し、太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を

排すべく窓を禁止してほしい、といった請願だけでなく、このように逆手をとった行き過ぎた論法

[reductio ad absurdum]が目覚ましい感銘を生むことはない、といった現実まで、想い起こしておら

れるかもしれません。》

ナイト2012^1960、9頁

参考

「太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を排すべく窓を禁止してほしい」

バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(1801~1850)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書(1845年)

ロウソク業者の請願 Petition of Candlemakers - kurakenyaのつれづれ日記

https://kurakenya.hatenablog.com/entry/20101228

http://www.panarchy.org/bastiat/petition.eng.1845.html

http://bastiat.org/en/petition.html

返信削除フランク・ナイト社会哲学を語る―講義録 知性と民主的行動 単行本 – 2012/12/1

フランク ナイト (著)

《商品を買うことを容認してアメリカの労働者が貧しくなるのを防いだ、と言われております。人によ

っては、バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(1801~1850)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書を連想し、太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を

排すべく窓を禁止してほしい、といった請願だけでなく、このように逆手をとった行き過ぎた論法

[reductio ad absurdum]が目覚ましい感銘を生むことはない、といった現実まで、想い起こしておら

れるかもしれません。》

ナイト2012^1960、9頁

参考

「太陽からやって来る安い外国産の灯りとの破滅的な競争を排すべく窓を禁止してほしい」

バスティア[Claude F. Bastiat(1801~1850)フランスの経済学者]が面白おかしく模造

したロウソク製造業者の陳情書(1845年)

ロウソク業者の請願 Petition of Candlemakers - kurakenyaのつれづれ日記

https://kurakenya.hatenablog.com/entry/20101228

http://www.panarchy.org/bastiat/petition.eng.1845.html

http://bastiat.org/en/petition.html