Pessimism, Optimism and the Role of Intellectuals

The challenge of modernity is to live life without illusions and without becoming disillusioned… I'm a pessimist because of intelligence, but am an optimist because of will.

— Antonio Gramsci (1891- 1937)

Back on December 10, 2016, after 45 years of college teaching, I met my last class. The course was Intro to International Politics: How the World Works. After twelve weeks of exposing countless myths, fables, and misinformation the odds of changing the world seemed daunting at best. If ignorance is bliss, there were few blissful days in the course and early on I mentioned that my mother not infrequently referred to her oldest son as "Dr. Gloom and Doom!" Per usual, I felt responsible to leave my students with some sense of hope but it had to be honest and not mawkish, anemic, liberal bromides.

Although my classes were invariably discussion oriented, on that occasion I chanced the students would tolerate a mini lecture. After waiting a full minute to get their attention, I wrote Gramsci's aphorism on the board and took it as my point of departure. Here's a synopsis of my comments for your possible interest:

British historian E.J. Hobsbawm described Antonio Gramsci as "an extraordinary philosopher, perhaps a genius, probably the most original communist thinker of the 20th century in Western Europe." Born on the island of Sardinia into a recently impoverished family, Gramsci had experienced the conditions he was to write about. As a revolutionary socialist and co-founder of the Italian Communist Party, his effectiveness as a radical thinker, journalist, agitator and organizer led to his arrest and imprisonment by Benito Mussolini's fascist regime in 1926. The charge was treason — attempting to "undermine the Italian state."

Mussolini had once referred to Gramsci as "this Sardinian hunchback and professor of economics and philosophy" who possessed "an unquestionably powerful brain." At his trial the government prosecutor pointed directly at Gramsci and famously proclaimed, "For twenty years we must stop this brain from functioning" and that was sentence. The serious health problems that plagued Gramsci's entire life continued as he spent most of the remainder of his life in prison.

When his health deteriorated to a life-threatening situation he was moved to prison clinics in1933 and 1937. Just prior to gaining his freedom in April, 1937 he succumbed to a stroke at age 46. While in prison he wrote his justly famous Prison Notebooks (34 volumes) and 3,000 pages of handwritten notes.

In 1929, writing from his prison cell, Gramsci tried to put his youngest brother Carlo's fears to rest with these words:

You must realize that I am far from feeling beaten…it seems to me that… a man out to be deeply convinced that the source of his own moral forceis in himself — his very energy and will, the iron coherence of ends and means — thathe never falls into those vulgar, banal moods, pessimism and optimism. My own stateof mind synthesizes these two feelings and transcends them: my mind is pessimistic,but my will is optimistic. Whatever the situation, I imagine the worst that could happen in order to summon up all my reserves and will power to overcome every obstacle. [1]

For Gramsci "the crisis" of his time and by extension our own, arises from the fact that the old order is expiring but the new one cannot be born. In the intervening period, certain "morbid symptoms" emerge. Most importantly, there is no guarantee the new order will be better or worse than the present one and it could be catastrophically worse.

One need not look far today to justify pessimism of the intellect, for Gramsci's "morbid symptoms." Decision-making in the U.S. remains in the hands of massive private tyrannies; the systematic undoing of reformist concessions wrung from capitalists has accelerated; endless wars; millions of plant and animal extinctions; four decades of neoliberal ideology has produced an empathy deficit disorder of epic proportions; a record number of desparate refugees around the world; ecocide, euphemistically called "climate change" looms; the populist right is gaining political ascendency around the globe; political manipulation and manufacture of consent has attained unprecedented levels; the U.S. empire is in decline and therefore its incomparable power is even more dangerous; and with the world seemingly in its death throes, the minuscule radical left in this country shows unmistakable signs of ossification.

On a personal level, claiming to face things as they really exist mandates looking into the abyss and acknowledging that my life's work may have been extraneous, perhaps doomed to irrelevancy. Put another way, being right about so many things hasn't counted for nearly as much as I'd assumed when much younger. The awareness that my own government is responsible for most of the world's overt and structural violence is a background thrum in my life and often leaves me feeling like a stranger in my own country.

Based on extensive exchanges with Facebook friends I know I'm hardly alone in this respect. I should quickly add that these numerous, far-flung contacts remain an essential source of sustenance for me and I encouraged my students to seek out friends and associations with shared commitments. If memory serves, I said that living life without illusions means being liberated from the brain-washing worldview imposed (and conveniently believed) by our rulers. That's life affirming and no small achievement. Finally, participating in struggles for justice brings rewards that simply can't be experienced anywhere else.

What then, is pessimism of the intellect? It's seeing the world as it actually exists, not some fantasy about how we'd like it to be. It means not accepting things at face value and doubting what we've heard since childhood in the absence of evidence. In short, it's pretty much what they'd heard before taking the class. In terms of optimism of the will, Gramsci means that humans have the capacity to overcome new challenges, to courageously move forward and create a better world in the face of very long odds. We can't predict the course of history but human agency is paramount and history is made by human will.

Here I hesitate to introduce the troublesome term "intellectual" but it bears directly on our subject. A major focus of Gramsci's work was on the role of intellectuals in organizing culture. Pessimism of the intellect requires discerning the truth about politics. However, Gramsci knew that "to say truth is revolutionary" but the reality is that most intellectuals speak untruths to the powerless. In his time, Gramsci observed this was so effective that "when truth is actually spoken, no one believes it." [2]

According to Gramsci it would be a grievous error to believe such matters are somehow only within the purview of individuals commonly referred to as "intellectuals." Gramsci wrote about what he called "organic intellectuals" who emerge out of their socioeconomic milieu. For the working class, arriving at a pessimism of the intellect and engaging in critical thinking are activities that can be performed by many different people depending on the occasion. It's not about pedigrees, those possessing 'superior powers of intellect,' certain writing skills or eloquence or special vocations. To be sure, affluence, leisure time and opportunity all factor in but "working class intellectual" is not an oxymoron.

"These organic intellectuals are distinguished less by their profession, which may be any job characteristic of their class, than by their function in directing the ideas and aspirations of the class to which they rightly belong." [3] This is what Gramsci meant by stating "all men are philosophers" or all individuals are intellectuals, in capacity if not always function. Different classes midwife their own intellectuals and the working class is fully capable of generating its own organic intellectuals in this broad sense of the term. The anthropologist Cate Crehan, a close student of Gramsci's work, reminds those of us intent on radical change must be mindful that counter narratives "emerge out of the lived realities of oppressed people's day-to-day living." [4]

I also reviewed Noam Chomsky's position that most people we call 'intellectuals' are a special class of people who are lavishly rewarded for imposing the ideas of those in power on the rest of us. And that "…the population should be anti-intellectual in that respect. I think that's a healthy reaction." He's suggesting that people need to develop an "intellectual self defense" against these 'intellectuals.' Chomsky goes on to assert, "My suspicion is that plenty of people in the crafts, auto mechanics and so on, probably do as much or more intellectual work than people in the universities…if by 'intellectual' you mean people who are using their minds, then it's all over society." [6]

For me, Paul Baran, the late Marxist professor of economics at Stanford University, adds to this more nuanced, more inclusive view when he asserts that to be an intellectual is to be a social critic, someone who identifies, analyzes and helps "to overcome the obstacles barring the way to the attainment of a better more humane, and more rational social order." [7] To be sure, such a person will be treated as a nuisance and a troublemaker by those in power and it takes courage and commitment to withstand the social pressure. However, echoing Gramsci, Baron makes the essential point that this understanding of "intellectual" includes all sorts of people from many walks of life.

What happens in the absence of optimism of the will? We already see it. Some people adopt a breezy, banal optimism that Gramsci describes as "nothing but a way to defend one's laziness, irresponsibility, and unwillingness to do anything." (Prison Notebooks, Number 9). More common is an enveloping of sense of impotence, fatalism, and withdrawing into oneself to fend off further despair, a voluntary disengagement that University of Texas journalism professor Robert Jensen identifies as "the ultimate exercise of privilege." [5]

Toward the end of the last session I said that during my career I'd tried to help students see through all the bullshit and grasp how the world works. I would not have remained a teacher if I hadn't wagered it should and could work much better. I reminded them of our first week's discussion that human nature has revealed a continuum of behaviors from the most wretched and cruel to the most compassionate and empathetic. At a minimum this means, in the words of Amin Maalouf, "There is a Mr. Hyde inside each of us. What we have to do is prevent the conditions that bring the monster forth." Call it optimism of the will or of the heart but to try to live life as we think humans should live —as the world should work — is a choice.

Chomsky put it this way: "You basically have two choices. You can say 'Nothing is going to change, so I am going to do nothing.' You can therefore guarantee that the worst possible outcome will come about. Or, you can take the other position. You can say: 'Look, maybe something will work. Therefore I will engage myself in trying to make it work and maybe there's a chance things can get better.' That is your choice. Nobody can tell you how right it is to be optimistic. Nothing can be predicted about human affairs…nothing." [8] It doesn't contradict Chomsky's assertion to conclude that failure to engage today will provide a definitive answer to Rosa Luxemburg's famous question: Will we be transitioning to socialism or barbarism?

(Thanks to Kathleen Kelly, my comrade and in-house editor, for her tough love critiques)

Notes

[1] Antonio Gramsci, Letters from Prison (New York: Harper & Row, 1973) pp.158-59.

[2] Prison Notebooks, Edited by V. Gerratano, Turin, 1975, p. 699.

[3] Selections From The Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci, edited and translated by Quentin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. (London: Eloc Books, 1991), p 131.

[4] Cate Crehan, Gramsci, Culture and Anthropology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), p.5.

[5] Although written fifteen years ago, there's arguably no more succinct and more accessible source for 'pessimist of the intellect but optimist of the will' than to consult Robert Jensen's Citizens o the Empire. (San Franciso: City Lights, 2004).

[6] Both quotes from Noam Chomsky, Understanding Power, Edited by Peter R. Mitchell and John Schoeffel, (New York: Harper & Row, 2002) p.96.

[7] Paul Baran, "The Commitment of the Intellectual," Monthly Review (May, 1961)

[8]Face to Face with a Polymath, Frontline, November, 2001.

-thumbnail2.jpg)

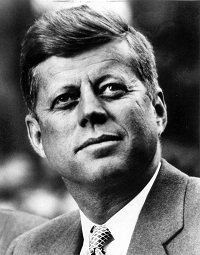

ケネディ大統領の暗殺にかかわったとされるクレイ・ショーに対する裁判には、無罪判決が言い渡されます。この訴えを起こしたジム・ギャリソン(ニューオーリンズ地方検事)は、その25年後に当時を振り返った著書の最後を、次のように結んでいます。

ケネディ大統領の暗殺にかかわったとされるクレイ・ショーに対する裁判には、無罪判決が言い渡されます。この訴えを起こしたジム・ギャリソン(ニューオーリンズ地方検事)は、その25年後に当時を振り返った著書の最後を、次のように結んでいます。